http://ndreview.nd.edu/archived-issues/ndr-43/

Oleg Okhapkin (1944-2008) was a Russian poet active in the cultural underground of Leningrad in the 1970s and 1980s. The underground, with its informal discussion groups and typewritten periodicals, offered an alternative platform for writers who eschewed compromise with the censor. The underground poets opposed the Soviet regime, which tightly regimented all cultural production, on aesthetic rather than straightforwardly political grounds. In Okhapkin’s case, his religious faith also played a role: he was a committed Orthodox believer, and his fascination with the biblical tradition is clearly reflected in his

Oleg Okhapkin (1944-2008) was a Russian poet active in the cultural underground of Leningrad in the 1970s and 1980s. The underground, with its informal discussion groups and typewritten periodicals, offered an alternative platform for writers who eschewed compromise with the censor. The underground poets opposed the Soviet regime, which tightly regimented all cultural production, on aesthetic rather than straightforwardly political grounds. In Okhapkin’s case, his religious faith also played a role: he was a committed Orthodox believer, and his fascination with the biblical tradition is clearly reflected in his

literary oeuvre. Yet religion remained taboo in official Soviet culture. In 1979, Okhapkin suffered reprisals for his involvement in an illegal Orthodox seminar for young people, a factor that contributed to the mental health issues that would stay with him for the remainder of his life.

It is tragic when a poet in the prime of his creative power is deprived of the opportunity to acquire a large readership. In this sense, Okhapkin shares the fate of his generation: during his lifetime, his work circulated in samizdat and, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, in a few editions that are now out of print. In 2013, his widow began compiling thematic

collections of his large oeuvre, three of which have been published so far.

Okhapkin began writing as a teenager and in the 1960s decided to dedicate himself to poetry, a vocation to which he remained faithful until his death. His work spans five decades. A sample comprising 100 poems, in Russian, can be found here:

http://www.religare.ru/25_861.html

Okhapkin was friends with many leading (underground) poets, including Joseph Brodsky. As a poet, he was versatile: in his oeuvre, we find versions of biblical stories alongside love lyrics and nature poetry. Indeed, his talent for using nature imagery in order to illustrate philosophical and spiritual realities places him in the tradition of Russia’s finest nature poets, such as Fedor Tiutchev, Boris Pasternak and Nikolai Zabolotsky. At the same time, Okhapkin was a product of his era and thoroughly postmodern in his tendency to combine vastly different registers and concerns. Scripture and myth intertwine with mundane concerns; Church Slavonic enlivens contemporary colloquial Russian. The influences palpable in Okhapkins’ work range from the 18th-century classic Gavrila Derzhavin to his slightly older contemporary Joseph Brodsky. Okhapkin had a gift for using words in order to give physical existence to abstract concepts; his language renders literally transparent that which is opaque. We might well find the poet arguing with his own soul during a stormy night, as if she was merely another embodied interlocutor, another friend.

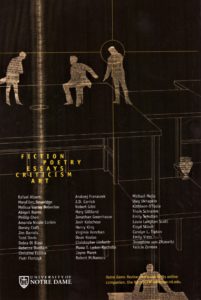

The Notre Dame Review is an independent, non-commercial magazine of contemporary American and international fiction, poetry, criticism and art. Their goal is to present a panoramic view of contemporary art and literature—no one style is advocated over another. They are especially interested in work that takes on big issues by making the invisible seen, that gives voice to the voiceless—work that gives message form through aesthetic experience.

The Notre Dame Review is an independent, non-commercial magazine of contemporary American and international fiction, poetry, criticism and art. Their goal is to present a panoramic view of contemporary art and literature—no one style is advocated over another. They are especially interested in work that takes on big issues by making the invisible seen, that gives voice to the voiceless—work that gives message form through aesthetic experience.

To the translator, Okhapkin presents a challenge. He remained formally conservative, and his poetry adheres to traditional patterns of strict rhyme and meter, a practice that is widespread in Russian poetry to the present day and requires creative solutions if the poems are to “work” for a contemporary English-speaking audience. It is my conviction that a translation

must communicate what it is that moves the poem. In Okhapkin’s case, the music of form is absolutely central to his writing. Strict rhyme can easily sound contrived in English. I hope that my metered versions transmit some of the vigour of the originals, and of their strangeness, too, in the best sense of the word – Okhapkin’s poets are strange because they make us see the world around us with fresh eyes. This is the first publication of Okhapkin’s poetry in English translation.

Josephine von Zitzewitz

© Notre Dame Review (USA): EXPANDED BIO (OLEG OKHAPKIN). Issue 43. Winter/Spring 2017

© Josephine von Zitzewitz

© «Russian culture»/2018