Any revolution among other things can be treated as a cultural space of myth making, hence producing a certain invariant of a Great Cultural Text consisting of a number of ‘smaller’ ones coded in accord with the aims and means of the actors in the ‘here and now’ format, on the one hand, and in the perspective of the future, on the other. In both cases, the revolutionary rhetoric is based on both verbal (slogans, appeals, talks and speeches, leaflets, newspaper articles, etc.) and non-verbal (the complete paradigm of body language; the natural, cultural and social landscape; ‘revolutionary’ actions; the existing and constructed mythology, etc.) means, applied in different ways by different acting parties and later on made historically ‘legitimate’ in memoirs and, finally, scholarship. The task of a memoirist is to secure the image of the event(s) present in his/her memory, the task of a scholar being to (re)interpret this image on the background of other data available on the topic. In the former case, one deals with memory-based (conditioned) translation of the events into a written verbal document and / or a non-verbal text; in the latter, with a retranslation of it into a piece of formal academic writing, both types of the text eventually contributing to further (re/de)construction of the initial ‘revolutionary’ language. The present paper based on various public and personal sources aims at analyzing ‘translations’ of the Russian 1917 revolutionary events (both February and October) texts from the radical language(s) of the immediate actors into the ones of Russian first wave émigré community.

Every revolution brings to life its negative double – a counterrevolution, each of them constructing its own myth and deconstructing that of the other party; both myths based on the same events treat them in the perspective of different axiological systems thus each presenting a mirror reflection of the other. To do it, they often use the same verbal and visual images and metaphors translating them into their own language of cultural and moral values and applying the same oppositions of ‘the order – the disorder’, ‘the legal – the illegal (i.e., the revolution – the coup)’, ‘the national – the international’ (the Russian – the Jewish – the Western, etc.), ‘the good – the evil’, ‘the beautiful – the ugly’, ‘the wonderful – the horrible’, ‘the hopeful – the disastrous’, ‘the sacred – the profane’, their strategies oscillating between heroization and deheroization, glorification and debunking, victimization and demonization, sacralization and desacralization, hailing and damnation.

February and October in Verbal Texts: Émigré Diaries and Memoirs

The standard revolutionary myth presents the events of the end of February – beginning of March 1917 highly positively, as ‘the Spring come true’, ‘The Great Bloodless Revolution’, the turning point in Russian history promising a long-awaited freedom for the people and great liberal future for the country. Emigré memoirists, however, representing all social classes, from the members of the Imperial family to high aristocracy to the military and the Navy to middle class people, also treating the events in the historical perspective as a turning point, regard it negatively, as the period of national shame [1], and as such – the beginning of the end, leading to total chaos and ruin of the country, even though some of them state that “at first nobody could predict all the tragic consequences with the fatal end” [2. P. 219]. Others, though, from the very start perceived it as “the precipice”, “the abyss”, and “the fatal borderline” [3. P 13; 4. P. 118; 5. P. 17; etc.]. In the third group of texts the presentation of events changes from highly or moderately positive at the first stage of the revolution to ambiguous to totally negative at its following stages. Elena Lakier, in February 1917 a student of Odessa Conservatory, starts with hailing the ‘revolutionary heroism’ and ‘adoring’ Kerensky and eventually comes to deconstructing her former heroes and presenting them as anti-heroes [6. P. 133-144]. Maria Germanova, one of the most famous actresses of the time, recalls that the majority of her colleagues at the Maly Theatre in Moscow were at first ‘quite reserved’ in their assessment of both the spring and autumn events, their reserve turning to ‘deep pessimism’ and feeling cheated and betrayed by the Provisional Government and Kerensky as time went on bringing about more and more disillusioning results. She admits that her own attitude towards Kerensky started as that of admiration, to change into deep disillusionment as things progressed from spring to summer to autumn and none of the major February political figures proved worth of the people’s trust and “displayed not a bit of either heroism and strong will or the wish to sacrifice themselves for the people <…> nothing great, reliable, or sublime we’d expected of them” [7. P. 196-197; here and in all other cases the translation of quoted Russian texts is mine – O. D.].

In most diaries and memoirs, the events are described as the beginning of total anarchy, an outburst of limitless debauchery, the triumph of the wild and senseless element of the rioting masses no one even tried to stop. Countess Bennigsen, a military nurse who had just come back from the front, describes the center of Petrograd on March 2nd as the horrifying chaos of cars rushing to and fro, tightly packed with soldiers armed with guns and red flags, aggressive and altogether very much unlike the soldiers she’d spent the previous three years among. There were also women in the cars, “armed with guns and machine gun cartridge belts, embracing the soldiers, waving red flags, shouting loudly. <…> People in the streets looked frightened; the yardmen were shutting the gates. <…> There were a lot of drunkards and outlaws, too, and something frightening in the air” [8. P. 166]. In fact, the collective image of the revolutionary masses presented in this diary entry is that of individuals who have rejected their individuality for the ‘class solidarity’ as a result having turned into human beings who have lost their humanity in favour of literal and social machinery. Inseparable from their armour and glued to their cars, roaring in unison with them, these ‘lost people’ are a perfect collective metaphor of the so called ‘machine-man’, amoral and non-human, regarded as a sign of the Apocalypse come true.

Valentina Shelepina, a low middle class woman and since 1914 also a front nurse who had come to Petrograd at the beginning of 1917 and worked in the Hostel for injured soldiers (Obshezhito uvechnykh voinov), described those days very much in the same way, all stylistic differences conditioned by social and cultural ones considered. February and October events have contaminated in her consciousness and her memory as some long-term horror, with the old life devastated and all customary civilized norms gone: “There was disorder in the whole city. People were arrested, put to prison, and shot; quite a few never came back home. <…> One couldn’t be out in the street even during the daytime; at night, houses were raided, and there were a lot of arrests, and people never returned. Their fate was prison and execution” [6. P. 16].

The naval officer Boris Bjorkelund recalls February as a mixture of “gun and machine gun shots, roaring and howling of the crowd, singing of revolutionary songs interspersed with shouts ‘Hurrah’, huge crowds on Nevsky”, qualifying the whole thing as “the riot” [9. P. 22-25, 28, 30]. Grand Duke Gavriil writes about “chaos, lawlessness, and the dictatorship of the masses”, with shots never stopping and very little idea of who was fighting whom. The city was “conquered by criminal gangs wandering around the city and robbing shops and warehouses. At night, they gathered at street corners around fires and amused themselves shouting songs and shooting everyone who dared appear in the streets of the doomed city. They also robbed wine cellars and got drunk. They felt complete masters of the situation” [2. P. 239; the italics are mine – O. D.]. The picture presented reads as an acute dramatic allusion to late ancient Rome raided by the barbarians whose aim was ruin, murder, loot, and total destruction of the state of things traditionally perceived as culturally normal. Senseless violence becomes the routine of revolutionary ‘freedom’.

Red and gray are the two predominant colours in these and numerous other accounts, the former being the colour of the illegitimate red flags and blood of the innocent victims, the latter serving as a metaphor of the soldiers’ mass in the streets and their favourite treat – sunflower seed and its skin they spat out onto the pavements. Another omnipresent metaphor is that of dirt and destruction that seemed to have flooded both the capitals as well as provincial places almost overnight. Recalling October in Moscow, for instance, Germanova states that “in a few days, Moscow, our voluptuous beauty, turned into an ugly beggar, as if some revengeful fiend stamped upon its beauty and chastity and crushed them with furious anger” [7. P. 199].

The double metaphor of sacrifice and victim is used quite extensively to deconstruct both the myth of “the great bloodless” (February) and the one of “the liberating socialist” (October) revolutions. Among other things, memoirists juxtapose the revolutionary rhetoric of the funeral of the imaginary “victims” organized by the Petrograd Soviet to the real horror of the slaughter of the policemen and officers in the capitals and the provinces in early March 1917. Bjorkelund gives a complete list of the naval officers killed on March 3rd – 5th in Petrograd, Kronshtadt, and Helsingfors [9. P. 57-58], while wives and widows of the officers recall those days as “full of the most outrageous horror ever experienced” [10. P. 1-5]. Doctor Lodyzhensky writes of the danger wounded front officers were facing in his hospital in Kiev starting from March [4. P. 118 and the foll.]; to add to this account, Princess Vadbol’skaya, the head nurse of the same hospital, describes all the difficulties of supplying those officers with new papers presenting them as soldiers to save their lives [5. P. 17]. Shelepina tells the half dramatic-half detective story of helping numerous officers leave Petrograd after the October coup to save them from arrests, torture, and executions [6. P. 19, 21, 23-25]; Marya Slivinskaya, Colonel Slivinsky’s wife (both of them were members of Vassily Shul’gin’s organization “Azbuka” and are mentioned in his memoirs [11. P.285, 328]) describes the atrocities in Kiev and Odessa in 1917 – 1919 [6. P. 74-95. 97-99]; Lakier also recalls the horrors and hardships of life in Odessa after the coup [6. P. 146-158]. Human life seemed to have lost its value, to say nothing of such ‘obsolete’ things as dignity, honour, and Christian feeling of brotherhood. All memoirists describe intentional aggressive dehumanization used by the new regime as the basic every-day strategy to curb any opposition, and the “new revolutionary morality” which from the traditional human point of view was arrogantly immoral.

Mikhail Osorgin in one of the final chapters of his “Kniga o kontsakh (The Book about the Ends)” depicts the post-February return of former political emigres from Europe to Russia, travelling through all the fronts in the infamous ‘sealed carriage’. Osorgin deconstructs both the idea of their long struggle for ‘the proletariat dictatorship’ and the Bolshevik image of Lenin as ‘the most human of the human beings’. The former, to his mind, had been used as a ‘toy’ nobody really believed in, but it was to become the only real remaining thing after the October coup, with those who had struggled for freedom becoming ‘butchers of the people’, their true ideology represented by the figure and deeds of ‘the Simbirsk nobleman’, whom emigres of the next generation would call a villain but who in fact “was nothing of the kind – he just was not human” [12. P. 331-334]. Tyrkova-Williams recalls her conversation with Lenin as early as 1904, when both of them were revolutionaries struggling for freedom, even though belonging to different social circles and political parties. She predicted that after the beginning of the revolution they would all be hanged by the ‘freed’ people; Lenin retorted: “It’s you who’ll be hanged; as for us, we’ll lead the revolution and the people” [13. N. p.].

As is obvious from the above said, the majority of émigré witnesses qualify the February events as a riot, “senseless and merciless”, to quote Pushkin’s famous line; from their point of view, February was the beginning of the end, pushing the country and its people to the precipice [2. P. 109]. The October event, called by the memoirists ‘a coup’ as opposed to ‘the revolution’ of the Bolshevik rhethoric, is unanimously described as the abyss of shame, grief, and hopelessness and the beginning of the Civil war with all its atrocities and tragic outcome.

Visual Texts: Civil War White Armies’ Posters

All White armies, anti-Bolshevik parties and counterrevolutionary governments relied heavily on propaganda serving two majour aims. One was purely pragmatic – to win the population over to their side thus ensuring the people’s support and the source of extra drafting. The other was ideological and hence vital for the former – to deconstruct the enemy’s myth of the Great Revolution for the Good of the People presenting it as a set of lies and its ‘fathers’ as a pack of unlawful impostors caring neither for the people nor for the country but for power with all its benefits. Posters issued by numerous information agencies and news groups abundant in all the armies served as the most convenient propagandist means combining verbal texts with visual images.

The language of the posters is blunt, their meaning quite obvious, alluding to generally recognizable and culturally heavily loaded symbols as well as images and appealing to certain feelings based on certain values. In some cases the general visual idea might be borrowed from that of the enemy’s or a third source.

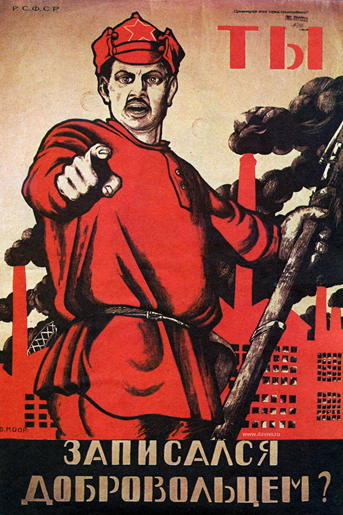

This was the case with the poster “Why Aren’t You in the Army?” (Dobrov), issued by the Volunteers’ Army in 1919. On the one hand, it was a cultural quotation referring to the famous Italian World War I poster – Luciano Mauzan’s “Do Your Civil Duties” (1917); on the other, Dobrov’s poster was obviously used as the basis for the most well-known Soviet Civil War poster by Moor “Have You Conscripted?” (1920). The target audience and the main political/ideological message of all the three of them is similar: a citizen should do his duty towards the country when the country needs it. The language, though, conditioning the emotional impact, is quite different. The quiet khaki as the base colour of the Italian original and Dobrov’s poster vs the aggressive red of Moor’s one combined with differences in composition and body-language produce the effect of the persuasive appeal vs the power-loaded demand. “The Winner” (c. 1918, anon.) could be regarded as another example of cultural borrowing of the sort: a Bolshevik ‘hero’ in the center presented as a cruel Oriental-looking savage, his foot on the dead body of the Father / Motherland, with a murdered baby on the right, resembles numerous World War I posters picturing enemies as blood-thirsty monsters.

«Отчего вы не в армии?». Автор неизвестен. Плакат Добровольческой армии – 1919

Лучано Мауцан. «Выполните все свои обязанности!». Итальянский плакат – 1917

Дмитрий Моор (Дмитрий Стахиевич Орлов). «Ты записался добровольцем?» – 1920

«Победитель». Автор неизвестен – около 1918

The values of the Reds and the Whites being radically different, the posters present two opposite texts (that is, two opposite myths), each of them semiotically negating the other even though more often than once using the same concepts and symbols (Mother Russia, the Russian people, etc.), Biblical allusions, Russian historical figures, and relying on the same strategies, methods and devices. A multilayered synthesis of all the above mentioned as well as the traditional image of the opposite party as the Other, hence – the Enemy, is presented in Ivan Bilibin’s classic poster “How the Germans Were Letting Out the Bolshevik onto Russia” (April – July 1917). The poster is deconstructing the Bolshevik myth of the Revolution as the natural result of Russian history, that is, a purely Russian ‘national’ phenomenon meant to save the country and its people, and presenting it as something implanted from without by Russia’s worst enemy to ruin the country. Heavily stylized to the Russian folk lubok tradition in both the verbal[1] and the non-verbal parts, the poster in many respects sets the paradigm of themes, images, symbols, characters, devices, and techniques for both White and Red posters of the Civil War period.

Иван Билибин. «О том, как немцы большевика на Россию выпускали» – 1917

Ironic (bordering on satirical and grotesque) reversal is one of the most often stylistic devices, used in the posters; see, for instance, “Federal Soviet Monarchy” (Omsk, s.a., anon.), “Peace and Freedom in Sovdepia” (OSVAG, 1919, anon), “Death, Hunger, and Desertion” (1919, anon.), “The Bolshevik Punitive Forces” (Kharkov, 1919, anon.), “What Is Bolshevism Bringing to the People” (A. Kucherov, 1918), “Lenin and Trotsky as Doctors for the Sick Russia” (Rostov-on-the- Don, c. 1918, anon.), “Dashing Work of the Red-International Army” (Argus <A. Gromov>, s.a.). All of these as well as lots of others deconstruct the Bolsheviks’ myth of the aims of the revolution, juxtaposing their promises and propaganda to the true picture of what they really brought to Russia and its people and mocking the official name of the new state and its basic slogans. One of the essential characteristics of the posters is the thoroughly highlighted non-Russian look of the leaders and ‘soldiers’ of the Soviet rule to stress the foreign / international rather than the national origin of it, as well as its oppressive nature. In the majority of posters, Mother Russia is sadistically tortured and / or cruelly murdered, both literally and metaphorically, by either personalized or collective non-Russian oppressors, uncivilized and non-human. Apocalyptic images are used both as recognizable Christian allusions and visual means of depicting the danger and warning against it.

«Федеративная советская монархия». Омск. Типография Акционерного Общества Р.О.П.Д.

«Мир и свобода в совдепии». Харьков. Плакат ОСВАГа – 1919

«Смерть, голод и опустение…» — 1919

«Большевистские карательные отряды». Харьков – 1919.

А. Кучеров. «Что несет народу большевизм» – 1918

«Ленин и Троцкий врачи больной России». Ростов-на-Дону – около 1918

Аргус (Алексей Матвеевич Громов). «Лихая работа красной интернациональной армии Ленина и Троцкого»

Trotsky and Lenin (in this order of priority) play the part of the two main villains of the White armies posters; the fact that they were also the main heroes of the Soviet posters makes their images very convenient for comparative cultural analysis as instances of translating different values by very much the same means even though used in radically different ways.

«Вот он! Виновник пыток и смертей, убийца женщин и детей!»

Троцкий — Георгий-Победоносец, убивающий змея контрреволюции – 1918

In the Whites’ poster “Here He is, the one guilty of torture and deaths, the killer of women and children” (c. 1918, anon) two classic cultural artefacts are quite obviously alluded to. The first one is the story of Mefisto, that had brought to life numerous philosophical, literary, pictorial, musical and theatre texts, having become a densely culturally loaded semiotic phenomenon. The second artefact is Vassily Vereshchiagin’s world-famous anti-military picture “The War Apotheosis” (1871) ironically ‘dedicated’ by the artist “to all conquerors – past, present, and future”. As a result, this contaminated Mefisto-cum-“The War Apotheosis”- allusion deconstructs the ‘sacred’ figure of the Soviet pantheon visually desacralizing it.

In the Soviet poster “Trotsky as St George killing the Hydra of the Counterrevolution” (1918) it’s the Russian and the all-Christian sacred figure and text that are desacralized and mockingly used to highlight Trotsky’s status, power, and omnipresence as a guarantee of the status, power, and omnipresence of the party which he is metonymically used to represent. The strategy of the negative, sacrilegious usage of the story of St George and his heroic deed proved quite productive and as such long-lived in Soviet propaganda: Pamela L. Travers recalls seeing one of its versions in one of smaller chapels of St Basil’s Cathedral during her Moscow tour in 1932. It was somewhat changed, though, to match the actual political realia of the time: instead of Trotsky, there is a whole Soviet pantheon, with Lenin in the centre, followed by Stalin, Kalinin, Molotov and Co (14. P. 92-93). From the point of view of cultural translation, this is a clear case of double successive adaptation with all censorship demands followed: first the Christian cultural text is adapted to the reality of the early Soviet period, then the resulting cultural ‘product’ is adapted to the political situation of the 1930s Soviet Union.

As for true heroes of the White Movement, they were presented in the posters either as abstract non-personal images of typical Russian folk bogatyry, or in a personalized way, in the form of highly aestheticized portraits of real people (generals, army commanders, officers and soldiers known for their heroism; very rarely – political figures). In the anonymous poster “For Rus’!” (1919) published in Omsk by the Artistic Department of the Commander, that is, Admiral Kolchak, the hero is depicted as a typical character of a Russian bylina, i.e., heroization is based on the appeal to traditional Russian cultural values and folk imagery. In “The Generals’ Posters” series published by the Russian Southern Forces (VSUR) in 1919, army commanders are represented in a somewhat Russian folk style with ample verbal texts describing their deeds; see, for instance, the poster showing General Wrangel’ as the Caucasian Army Commander.

«За Русь!». Омск. Издание художественного отдела Осведверха. Автор неизвестен – 1919

«Генерал-Лейтенант Петр Николаевич барон Врангель» из серии «генеральских» плакатов. ВСЮР. Автор неизвестен – 1919.

«Командующий Кавказкой Армией генерал-лейтенант барон Петр Николаевич Врангель». Автор неизвестен. – 1919

What is obvious in these as well as in a lot of other posters is a strategy of triple translation applied to both constructs and readings of the implied message, i.e.:

- the verbal and visual texts mutually ‘translate’ each other, reciprocally adding to each semiotic layer and making the whole message evident;

- the concepts and symbols are ‘translated’ to fit into the paradigm of essential values meaningful for each party in a given period of time;

- the values are translated into the language of a certain axiological, cultural, ideological, and political discourse.

Список литературы

- Великий князь Гавриил Константинович. В Мраморном дворце: Из хроники нашей семьи. – СПб.: Издательство «Logos»; Дюссельдорф: «Голубой всадник», 1993. – 288 с.

- «Позорное время переживаем»: Из дневника великого князя Андрея Владимировича / Публ. В. М. Хрусталева и В. М. Осина // Источник. 1998. № 3. C. 31–61.

- Тхоржевский И. И. Последний Петербург: Воспоминания камергера. – СПб.: Издательство «Алетейя», 1999. – 256 с.

- Лодыженский Ю. И. От Красного Креста к борьбе с коммунистическим Интернационалом. – М.: Айрис-пресс, 2007. – 576 с.

- Вадбольская Н. В. Воспоминания Нины Владимировны Вадбольской // Архив русской и восточно-европейской истории и культуры (Бахметевский) Колумбийского университета г. Нью-Йорка. Ms Vadbol’skaya. – 42 c.

- «Претерпевший до конца спасен будет»: Женские исповедальные тексты о революции и гражданской войне в России / Сост., подгот. текстов, вступ. ст. и примеч. О. Р. Демидовой. – СПб.: Издательство Европейского университета в Санкт-Петербурге, 2013. – 262 с. (Эпоха войн и революций. Вып. 2).

- Германова М. Н. Мой ларец с драгоценностями: Воспоминания. Дневники. – М.: Русский путь, 2012. – 448 с.

- Беннигсен Ф. В. Записки // «В мире скорбны будете…». Из семейного дневника А. П. и Ф. В. Беннигсенов / Публ., вступит. заметка, примечания О. Демидовой // Звезда. СПб. 1995. № 12. С. 165–

- Бьёркелунд Б. И. Воспоминания. – СПб: Алетейя; Международная Ассоциация «Русская культура», 2013. – 168 с.

- Дон. Н. С. Мои воспоминания // Архив русской и восточно-европейской истории и культуры (Бахметевский) Колумбийского университета г. Нью-Йорка. Ms Don. – 25+14+17 c.

- Шульгин В. В. 1917 – 1919 / Предисловие и публикация Р. Г. Красюкова. Комментарии Б. И. Колоницкого // Лица: Биографический альманах. 5. – М.: Феникс; СПб.: Atheneum, 1994. C. 121–

- Осоргин М. Книга о концах // Осоргин М. Свидетель истории. Книга о концах: Романы. Рассказы / Сост., примеч., вступит. статья О.Ю. Авдеевой. – М.: НПК «Интелвак», 2003. – 496 с.

- Тыркова-Вильямс А. В. Воспоминания. То, чего больше не будет. – М.: Слово / Slovo, 1998. – 560 c. URL: http://mirknig.su/knigi/belletristika/61125-vospominaniya-to-chego-bolshe-ne-budet.html (дата обращения 20.05.2017).

- Трэверс Памела Л. Московская экскурсия. – СПб.: Лимбус-Пресс, ООО «Издательство К. Тублина», 2017. – 288 с.

References

- Velikii kniaz’ Gavriil Konstantinovich. V Mramornom dvortse: Iz khroniki nashei semji [Grand Duke Gavriil Konstantinovich. In the Marble Palace: From Our Family History]. – SPb.: Izdatel’stvo «Logos»; Düsseldorf: «Goluboi vsadnik», 1993. – 288 р.

- «Pozornoe vremja perezhivaem»: Iz dnevnika velikogo kniazia Andreja Vladimirovicha / Publ. V. M. Khrustaleva i V. M. Osina [«We’re Living Through Shameful Times» From Grand Duke Andrej Vladimirovich’s Diary / Publ. by V.M. Khrustalev and V.V. Osin] // Istochnik, 1998. № 3. P. 31–61.

- Tkhorzhevskyi I. I. Poslednyi Peterburg: Vospominanija kamergera [The Last Petersburg : A Chamberlain’s Memoir]. – SPb.: Izdatel’stvo «Aleteja», 1999. – 256 p.

- Lodyzhenskyi Ju. I. Ot Krasnogo Kresta k bor’be s kommunisticheskim Internatsionalov [From the Red Cross to the Struggle against the Communist International]. – M.: Airis-press, 2007. – 576 p.

- Vadbol’skaya N. V. Vospominanija Niny Vladimirovny Vadbol’skoi [Nina Vladimirovna Vadbolsky’s Memoirs] // The Archive of Russian and East-European History and Culture (Bakhmeteff), Columbia University, New York. Ms Vadbol’skaya. – 42 p.

- «Preterpevshii do kontsa spasen budet…»: Zhenskie ispovedal’nye teksty o revolutsii I grazhdanskoi voine v Rossii / Sostav, podgotovka tekstov, vstupitel’naja statja i kommentarii O. R. Demidovoi [«He Who Suffered to the End Shall Be Saved»: Female Confessional Texts about the Revolution ans Civil War in Russia / Compiled, edited, with a foreword and commentary by O. R. Demidova]. – SPb.: Izdatel’stvo Evropeiskogo universiteta v Sankt-Peterburge, 2013. – 262 p. (Epocha voin i revolutsij. Vyp. 2).

- Germanova M.N. Moi larets s dragotsennostiami: Vospominanija. Dnevniki [My Jewel Casket: Memoirs. Diaries]. – M.: Russkii put’, 2012. – 448 p.

- «V mire skorbny budete…». Iz semeinogo dnevnika A. P. i F.V. Bennigsenov / Publikatsija, vstupitel’naja statja I kommentarii O. R. Demidovoi [«You Shall Be Mournful in the World…». From A. P. and F. V. Bennigsens’ Family Diary. Publ., with a foreword and commentary by O. Demidova] // Zvezda. SPb. 1995. № 12. P. 165–176.

- Bjorkelund B. I. Vospominanija [Memoirs]. – SPb.: Aleteja; Mezhdunarodnaja Assotsiatsija «Russkaja kul’tura», 2013. – 168 p.

- Don N. S. Moi vospominanija [My Memoirs] // The Archive of Russian and East-European History and Culture (Bakhmeteff), Columbia University, New York. Ms Don. – 25+14+17 p.

- Shul’gin V.V. 1917 – 1919 / Publikatsija I vstupitel’naja statja R.G. Krasikova. Kommentarii B.I. Kolonitskogo [1917 – 1919. Published and with the foreword by R.G. Krasiukov. The commentary by B.I. Kolonitsky] // Litsa: Biografichesky almanakh. 5. M.: Feniks; SPb.: Atheneum, 1994. P. 121–328.

- Osorgin M. Kniga o kontsakh / Sostav, vstupitel’naja statja I kommentarii O.Ju. Avdeevoi [The Book about the Ends] // Osorgin M. Svidetel’ istorii. Kniga o kontsakh: Romany. Rasskazy [A History Witness. The Book about the Ends / Comp., with a foreword and comment. by O. Ju. Avdeeva]. – M.: NPK Intelvak, 2003. – 496 p.

- Tyrkova-Williams A. V. Vospominanija. To, chego bol’she ne budet [Memoirs. What Will Never Be Again]. – M.: Slovo/Slovo, 1998. – 560 p. URL: http://mirknig.su/belletristika/61125-vospominaniya-to-cheg0-bolshe-ne-budet.html (accessed 20.05.2017).

- Travers Pamela L. Moskovskaja ekskursija [Moscow Excursion]. – SPb.: Limbus-Press, OOO «Izdatel’stvo K. Tublin», 2017. – 288 p.

Примечания

Впервые опубликовано в: История повседневности. 2017. № 3 (5). С. 40–49.

[1] «На святую нашу Русь / Прилетел заморский гусь: / Полузмей, полуворона, / А на маковке – корона. / Что за чудище сидит, / Воет, свищет и шипит? / И, тараща свои бельма, / «Я орел, — кричит, Вильгельма! / Всех хочу я покорить, / Всех согнуть и раздавить!» / <…> Там у русского народа, / Говорят, теперь свобода. / Ну, так выкинем мы штуку, / Заберем в свои их руки! / Вылезай-ка, большевик, / Подымай в России крик! / Не вели войскам сражаться, / Вели с немцами брататься! / <…> И проклятый большевик / Свое дело сделал вмиг. / Поклонился черной птице, / Смуту сеял, фронт открыл, / Всей России яму рыл».

© Ольга Демидова (Olga Demidova), 2017, 2019

© НП «Русская культура» (NP «Russian culture»), 2019